Article

Article

Prior to the emergence of Donald Trump and his often incoherent articulation of an "America First" foreign policy, the United States maintained a clear strategic commitment to extended nuclear deterrence. The basic principle was straightforward: to deter attacks on its allies in Europe and Asia, the US developed the capability—and projected the political will—to respond to aggression with nuclear force. At the height of the Cold War, when NATO was conventionally outmatched by the Warsaw Pact, American nuclear doctrine for Europe included not only the threat of retaliation against a Soviet nuclear first strike but also the option of nuclear first use in response to a large-scale conventional attack.

Given the Soviet Union’s own vast arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles and strategic bombers, any US defense of its allies risked triggering a nuclear strike against American cities. This raised persistent doubts about the credibility of US commitments: would Washington truly risk New York or Chicago to defend West Berlin or Tokyo? These concerns animated much of the strategic debate throughout the Cold War.

Extended nuclear deterrence served a second purpose. In addition to deterring Soviet aggression, it functioned as a tool of nuclear non-proliferation. By offering credible security guarantees, the US was able to dissuade key allies—most notably West Germany and Japan—from developing nuclear arsenals of their own. Keeping the nuclear club small was seen as vital to global stability, and it preserved US influence as the linchpin of Western security.

Despite its verbal commitments, doubts about the credibility of extended deterrence persisted. During the crises over Berlin (1958–62) and the Taiwan Strait (1954–58), both Moscow and Beijing tested US resolve. French President Charles de Gaulle was also deeply skeptical of US willingness to risk a nuclear strike on the American homeland for the sake of an ally. Disillusioned by US support for France in Indochina and Algeria, de Gaulle announced the creation of an independent French nuclear force—la force de frappe—in 1959.

Given such doubts, Washington invested heavily in convincing both adversaries and allies that it was prepared to accept real risk to uphold its commitments. The Euro-missile crisis of the late 1970s and early 1980s is a case in point. In response to the Soviet deployment of SS-20 intermediate-range missiles in Eastern Europe, the US deployed its own Pershing II and ground-launched cruise missiles on NATO territory. Though these deployments did not alter the overall nuclear balance (the Soviets still could destroy the United States many times over), they were intended to send a political message: the US would put its own forces—and population centers—on the line to defend Europe. Meanwhile, in Asia, Washington pressured Taiwan to abandon its nuclear weapons program in exchange for security assurances. A Taiwanese bomb would have complicated US efforts to normalize relations with the People’s Republic of China and could have triggered a wider arms race involving Japan and South Korea.

Was the strategy of extended nuclear deterrence a success? At least it did not obviously fail. Despite repeated crises, the Soviet Union never directly attacked the territory of a European ally of the United States. The same cannot be said of Hungary or Czechoslovakia, which faced Soviet invasions in 1956 and 1968, respectively. Moreover, the British and French nuclear forces remained limited and served more to complement than replace US capabilities. Today, however, the foundations of nuclear stability in Europe are weakening under the pressure of major geopolitical and technological shifts.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, accompanied by explicit nuclear threats, marks a clear rupture with both Cold War and post–Cold War norms. In 1975, the US and Soviet Union signed the Helsinki Accords, affirming the inviolability of European borders and renouncing the use of force to alter them—commitments Russia reaffirmed in the Charter of Paris (1990), the 1992 Helsinki Summit Declaration, and the Budapest Memorandum (1994). Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, both superpowers largely avoided overt nuclear threats and pursued strategic stability through arms control treaties such as SALT, INF, and START. Today, Russia threatens a nuclear attack on a non-nuclear state whose security it has pledged to defend!

Russia’s nuclear posturing would be less alarming if Europeans still believed in the credibility of America’s nuclear umbrella. But Donald Trump’s return to the White House—given his deep skepticism toward NATO and open-ended defense commitments—has revived old fears of US disengagement. Would he truly risk a nuclear exchange to defend a European ally? His ambivalent stance on Ukraine—despite Kyiv having surrendered its Soviet-inherited nuclear arsenal in 1994 in exchange for US, UK, and Russian security assurances—has done little to inspire European confidence.

Meanwhile, Europe faces an increasingly complex and unstable global nuclear landscape. The erosion of arms control regimes, China’s rapidly expanding arsenal, and the uncertain future of Iran’s nuclear program after Israeli and American military strikes in June all raise urgent questions for European security. These geopolitical shifts coincide with disruptive technological advances—high-precision strike capabilities, enhanced surveillance, missile defense systems, and artificial intelligence—that threaten the survivability of retaliatory forces and challenge the logic of Cold War–era deterrence.

In this emerging strategic environment, Europe can no longer rely on the stability conferred by a bipolar US-Soviet rivalry or the arms control architecture it produced. Instead, the continent must navigate a world of diffuse nuclear risks, rapid technological change, and uncertain American resolve—placing the future of European security in far more precarious balance than at any point since the Cold War. Identifying and evaluating the risks and benefits associated with various European responses to this changed reality is a strategic imperative that must include researchers, policymakers, and citizens.

Images: Keystone, Adobe Stock / rickray

Book

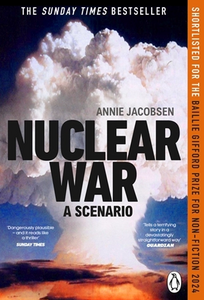

Up to now, no one outside of official circles has known exactly what would happen if a rogue state launched a nuclear missile at the Pentagon. Second by second and minute by minute, these are the real-life protocols that choreograph the end of civilisation as we know it. Based on dozens of new interviews with military and civilian experts, "Nuclear War" by Annie Jacobsen is at once a compulsive non-fiction thriller and a powerful argument that we must rid ourselves of these world-ending weapons for ever.

Book

"The Fragile Balance of Terror", edited by Vipin Narang and Scott D. Sagan, brings together a diverse collection of rigorous and creative scholars who analyze how the nuclear landscape is changing for the worse.