Article

Article

President Trump routinely stuns and bewilders many with the sheer intensity of his policies—from protectionism to rhetoric on territorial expansion involving Greenland and even Canada; from deregulation and efforts to streamline government efficiency to frontal attacks on established narratives like sustainability and DEI, and venerable institutions like Harvard.

Conventional economic and political science theories seem inadequate to make sense of the current upheaval. At the same time Trump’s actions often appear rooted in personal experiences and psychology. Perhaps they are a reaction to the traumas associated with his entry into politics as an outsider, such as the sense of unfair treatment surrounding his double impeachment. Or maybe it goes deeper: he still seems to operate like the ambitious developer, the upstart from the Jamaica Estates neighborhood of Queens, striving to break into elite Manhattan circles he himself describes in his Art of the Deal. And yet, there must be an alternative framework for sensemaking—one more insightful and relevant to this moment—because once the dust of the 47th presidency settles, the question remains: will America emerge stronger and more prosperous than it already is, or fundamentally weaker?

While institutional theory is well established and explains development, this piece focuses on one specific cause of institutional change. Trump, and what his power achieves, are the ultimate proof that elites do matter. Elites, their varieties and traits, as well as their networks have been amply profiled, for instance by Bühlmann et al. in the World Elite Database (WED). The essential next step is to link the elite coalitions to their respective business models - a business model being “how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value” (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). Moreover, a business model is about strategy (Gassmann, Frankenberger, & Csik, 2020) and, from a sustainability perspective, its key component ought to be whether it is value-creating or value-extracting. The elite theory of economic developmentargues that existing economic theories and even their associated econometric models will benefit by systematically incorporating the critical dimension of GDP origination: elite-driven sustainable value creation, and its opposite, rent seeking. Let’s apply this idea to Trump’s America.

Elite business models are defined as those with the highest impact in society, those who move the largest amount of national income (GDP). They are visible and present in the daily news. They include the “Magnificent Seven” (Hartnett, 2023) and the “crypto bros”, Big Oil and the renewable energy sector, other important coalitions part of Big Tech, Wall Street, Big Food, as well as the education establishment, civil services, labor unions, political parties, the media. Elites are necessary for progress and all elites both create and extract value. What matters for development is the proportion in which they do so.

The absolutist lens of the elite theory is unconcerned about the personal characteristics of elites or their preferred narratives, the analytical focus, is their business model; the degree to which they create value or appropriate value that they do not create. Vilfredo Pareto theorized about elite circulation in The Rise and Fall of Elites. The point is that the more dynamic intra-elite contests are, the higher the likelihood that emergent value-creating business models rise to the top. Will Trump—the maverick outsider becoming president—oversee the kind of vibrant and intense intra-elite contestation that brings forth inclusive institutional change?

The relevant contests in the political economy are when opposing coalitions compete with distinct business models. For example, carbon-based energy vs renewables, or the Biden establishment vs the Trump coalition for the presidency. Upon victory by one or the other side subsequent rounds of nested battles emerge with new contests within the camps: among renewables (e.g., solar vs nuclear) or within the Trump coalition itself (as Elon Musk will confirm). These internal struggles are productive when institutionalized, but damaging with excessive splintering and lack of elite cohesion. At present, the fragmentation dynamics within the Trump camp are striking and intriguing. For instance, are the so-called “tech bros”, pillar of the November 6 victory, losing influence with the alleged “Technipolar Moment” fading (Wooldridge, 2025)? Within the Trump Administration, divergent forces—often irreconcilable on issues such as trade, skilled immigration, anti-trust, government spending, or plain morals—are locking horns. The outcomes of their bargaining, disputes, and settlements will materialize in institutional arrangements. Rules, like those governing trade, AI, security, crypto, or subsidies, will have an impact globally. These changes might be lasting to the extent that Turmp’s core coalition manages elite cohesion or his critics’ warnings about an authoritarian drift prove correct.

To elucidate any country’s future, one must examine the micro-level elite business models that win, lose, and emerge from its intra-elite contests. Which ones are these in America under Trump and what are the contender’s respective sustainable value creation positions? One has to go beyond the deafening noise (such as the Epstein files) and focus on the numerous open fronts within the US elite system: Wall Street vs protectionist interests (stock markets used to dislike tariffs, see Watts, 2025); the rising tech bros vs the traditional military industrial complex (Kinder & Hammond, 2024); “Big Food” vs Robert Kennedy’s “Make America Healthy Again” (Temple-West, 2025); bitcoin and “pro-Trump” crypto investors vs those supporting the former policies of institutions like Securities and Exchange Commission or the Department of Justice (Rogers, 2025); see even the upcoming reference to Harvard vs trade schools (Kent, 2025). Having established the contest, one must assess the degree to which each of the parties will rely on value transfers (rent-seeking) vs value creation.

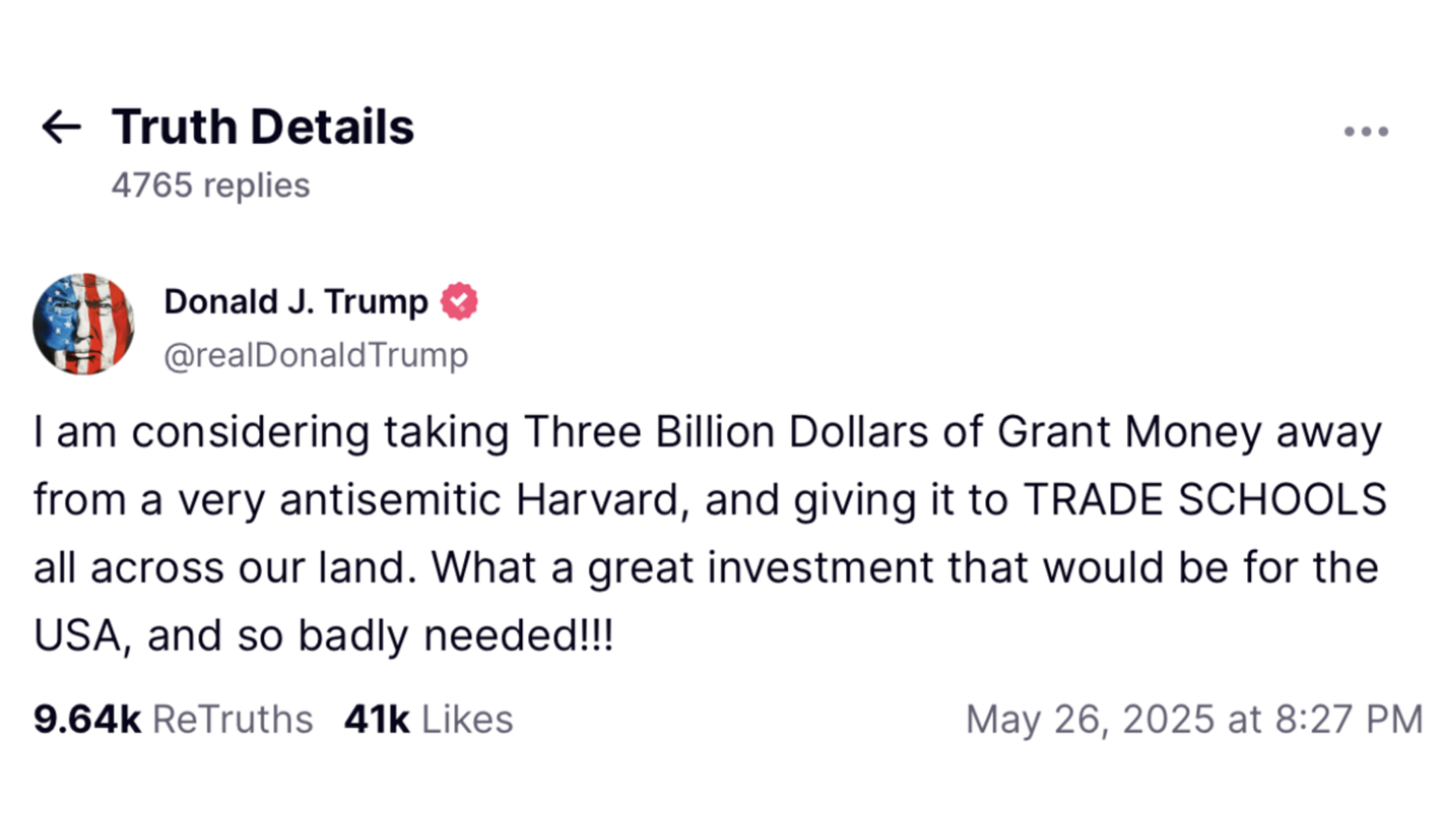

As one performs the analytics, it becomes clear that intra-elite competition is persistently messy and rarely linear. First, there can be agreements on policies across ideological chasms: Steve Bannon, the nationalist ideologue, agrees with Biden’s FTC Chair Lina Khan that Big Tech uses its power for rent-seeking and deserves antitrust lawsuits (Luce, 2025). Second, the victories of emergent elites are often the result of incumbent failures. The establishment that allowed Biden to run for president, and later appointed Harris, not only mismanaged the process—as recounted in Original Sin (Tapper & Thompson, 2025)—but also permitted the inflation wave that impoverished so many Americans and gave Turmp so many votes (which makes his own inflationary trade policies and monetary wishes all the more baffling). Third, when assessing the sustainable value creation signatures of elite business models versus non-elite interests, there are always trade-offs—as Trump (2025) contentiously highlights in a recent Truth Social post:

In Switzerland and Germany, one is rightly proud of the outstanding duale Berufsausbildung system. What do we think about taking three billion from Harvard and giving it to trade schools? Maybe Trump did not mean it, but if we had to make the hard choice, would we give the funding to Harvard or to trade schools?

As pointed out every old and new business model both creates and extracts value; it all hinges on the proportion—this is the core idea behind the Value Creation Rating (VCr) for firms (Casas Klett & Nerlinger, 2024). The implication is that when judging Trump, one must do so policy by policy, elite business model by elite business model. Assessing the VCr of the two alternatives for allocating the three billion dollars would surely offer insights in determining which option is more sustainable.

Likewise, each new piece of legislation brings with it a host of business models. Is the GENIUS Act—the ‘Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins Act’ signed into law this July 18th—a step towards the privatization of money (transferring a public good into private hands), or is it a contributor to more efficient and inclusive capital allocation?

Overall, seeking prosperity in America and anywhere fundamentally rests on the ability to distinguish between value creation and value transfers, and to determine the extent of each. Operationalizing this conceptual dualism is part of a project being conceived with my HSG colleague Guido Cozzi at the Institute for Economic Research and Policy (ERP-HSG), which aims to associate GDP origination with value transfers and integrate this information into economic models.

At the micro, firm-level, no one should be faulted for seeking value transfers—so long as they operate within legal frameworks. Elon Musk has every right to pursue subsidies, leverage the power of the US government to secure licenses for Starlink abroad, or advance regulation to support ventures like his extraordinary xAI. After all, this constitutes the vital energy that drives human development—provided, of course, that the right intra-elite checks and balances are in place and that ultimately power circulates effectively to those elites creating value.

In the Elite Quality Index (EQx2025), the United States ranks top in power (meaning that power is more transient, steadily circulating), and enjoys the highest levels of Schumpeterian creative destruction (see box). This is the main reason why, as Ferguson contends in Civilization: The West and the Rest (2011), one should never bet against the US. The American system, though it occasionally produces perplexing outcomes, remains anchored in robust political and economic competition and will not become authoritarian. Many of the coalitions of the former establishment—during the Obama and Biden presidencies—will soon regroup and eventually come to power again under new leadership and enhanced value creation models and narratives. This capacity for self-correction is precisely what makes the American elite system so extraordinary.

An optimist, armed with elite theory and faith in America, might say that once the dust settles on Trump’s elite circulation, the nation will be stronger. That assertion does not imply that the elite business models emerging under his presidency—in AI, trade, education, security, or government—are sustainable nor that they will prevail.

Image: Adobe Stock / DTM Media

Podcast

Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google DeepMind and Nobel Prize laureate, in conversation with Lex Fridman. One central focus of contemporary elite theory is artificial intelligence (AI), as emerging elites redefine the political economy. To understand the nature of the technology ahead, give it a listen.

Book

Europe is another focus of elite theory which examines the performance of its elite system. There is no stronger diagnosis of the continents’ challenges than Mario Draghi’s report, "The Future of European Competitiveness" (2024) that benchmarks Europe against China and the United States.

Book

To better grasp the broader aims of elite theory, it is worth taking a look at the now-classic work by Noble Prize winners. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson link inclusive institutions to prosperity.

Book

As we described our work on the publisher’s website: Institutions, the humanly devised constraints of economic activity, are outcomes of elite agency. Leveraging ideas from economics, sociology, politics, and strategic management, this book proposes an “elite theory of economic development”. The overarching goal is to foster sustainable value creation at the elite business model level. This work also aims to contribute to transformational leadership, and links are made to the annual Elite Quality Index (EQx), a measure of the value creation of national elites.