Article

Article

He's done it again. This time, it was the head of the Bureau of Labour Statistics who took the hit. Her crime: the latest labour market figures were disappointing. Only 73,000 new jobs were created in July – well below expectations. Even more problematic: the figures for the previous two months were revised downwards by almost a quarter of a million. What is normal practice in the world of economic statistics, as initial estimates are regularly revised, turned into drama in political Washington. US President Donald Trump fired Erica McIntyre and accused her on Truth Social of manipulating the figures for political reasons as a Democrat sympathiser. It was a political example of something previously only seen in unstable or authoritarian states. Or as former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen summed it up, "This is something you would only expect in a banana republic."

The incident marks a new level of escalation in the fight against facts – and against the concept of truth itself. Firing the messenger to get the message out of the world undermines the foundation of a democratic society: trust in institutions. The economic and political effects have already been seen in countries such as Argentina and Greece: in the long term, the manipulation of economic data leads to institutional upheaval, economic crises, and a massive erosion of trust in the government. Such developments are now also possible in the United States, once a beacon of democratic order and free markets. What is happening here is more than a warning sign. It is a sign that we are facing structural change – the establishment of a new form of political rule.

This new form of government can no longer be described solely with classic terms such as populism or authoritarian leadership. It is the result of a systematic shift in political communication and governance towards the logic of the attention economy. Its currency is attention, its tools: outrage, polarisation, and speed.

"My experience consists of what I am ready to pay attention to," said William James, one of the fathers of psychology in the United States, in 1890. He cleverly summed up what is even more true today: Only what gets people's attention is real. The most important information, the most critical opinion, is lost in nothingness when people turn their attention away.

Attention is now the most important and, in the meantime, also the scarcest commodity that people can exchange for recognition through perception. It is the core resource of an entire economic and political system, as architect and philosopher Georg Franck described in his 1998 book "The Economy of Attention".

Trump's use of social media to control attention is not an excess, but a blueprint. His second term in office is characterised by a hyperactive style of government. He rules by firing off a series of executive orders, through his permanent presence on his own platform, Truth Social. And through policies that are less and less guided by the Constitution or the rights of Congress, and more by the next wave of attention. Historian D. Graham Burnett has found an apt image for this: “Fracking people's minds.” Politics as high-pressure fuelling with manipulative messages or constantly drilling into attention channels to blow his own agenda into the minds of citizens.

This attention authoritarianism is the systematic result of years of preparation and strategic adaptation to a new media age. Steve Bannon, Trump's former chief strategist, summed it up bluntly: "Flood the zone with shit." Flood the public space with so much garbage for so long that no one can distinguish between facts and fakes anymore. In this cacophony, it is no longer truth that prevails, but volume. Whoever shouts the loudest rules. And whoever wants to continue ruling must continue to shout loudly. Politics thus becomes a permanent infomercial – a one-way street where Trump sets the agenda for the masses of welfare recipients.

In the United States, attention authoritarianism has replaced deliberative democracy. It thrives on the interplay of speech and counter-speech, on the willingness to listen, weigh arguments and find compromises. It is a slow, often laborious process, but one that creates consensus and stability.

Attention authoritarianism despises this slowness. It wants speed and simplification, because both serve polarisation. “Divide et impera” means rule through division. Many studies show that social media plays a significant role in this process of change. A survey by PEW Research from 2022 shows that the negative consequences clearly outweigh the positive in the United States. 64 percent of those surveyed see social media as a bad development for democracy. 79 per cent believe that it has divided the population more, and 69 per cent believe that people talk about politics in a less civilised manner.

These mechanisms have now also arrived in Europe. You don't have to look to Hungary or Italy. In Germany, France, and the Netherlands, too, we are seeing how debates are orchestrated on social media, spirals of outrage are generated, and misguided narratives are produced in real time. In Germany, a campaign orchestrated by right-wing online platforms with 40,000 posts on Platform X (formerly Twitter) against the candidate for the Federal Constitutional Court, Frauke Brosius-Gersdorf, contributed to her election to the German Bundestag being temporarily suspended. Brosius-Gersdorf has since withdrawn her candidacy.

The algorithms designed to promote “user engagement” and thus demonstrably contribute to the spread of hate speech have now become the infrastructure of authoritarian influence. Platform logic has hijacked state logic.

As a result, attention authoritarianism is gaining ground in democracies that have long considered themselves virtually perfect. The West was convinced that it had reached the end of history, as Francis Fukuyama described in his 1989 book of the same name. Liberalism and democracy seemed invincible. But this belief was deceptive.

The growth of the administrative state within the executive branch and military power, as US historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. analysed back in the 1970s, combined with other influences, leads to what he calls the "imperial presidency." Donald Trump is currently perfecting this model of government through the authoritarian management of attention.

Many Western democracies have failed to renew themselves. Political participation has been reduced to elections, and citizens feel increasingly alienated from a political system that appears bureaucratic, slow and self-absorbed. This need for simplicity, clarity and identity is an ideal breeding ground for the promise of attention authoritarianism.

The erosion of democratic structures does not happen overnight. It happens gradually, almost invisibly. Institutions are weakened, experts discredited, language poisoned. In the end, all that remains is a façade behind which the rules have long since changed. If we do not stop this development, decisions will no longer be made according to democratic rules, but by algorithms. And it does not ask for justice, but for reach.

Many Western democracies must begin to face this challenge and renew themselves from within. Citizens have a right to expect that the state, whose services they pay taxes for, will function properly. They can expect politics to legitimise itself through communication and not suffocate in PR spin. And they have a right to expect that the fundamental constitutional principles of a democracy can be discussed many decades after their establishment and, where necessary, renewed.

Former German Federal Constitutional Court judge Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde once said: “The liberal, secular state lives on conditions that it cannot guarantee itself.” Trust, civil courage, public spirit – all these things must be constantly renewed through the active revitalisation of political culture. Democracy is not a sure-fire success. It needs care, passion, and a willingness to self-correct.

No democracy can survive in the long term on non-committal virtual likes.

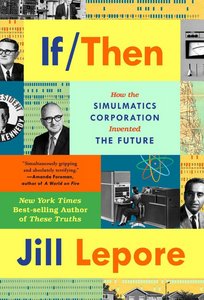

Book

This is a fascinating book that sheds light on early attempts to predict the future using data-driven forecasts and models – long before big data and social media dominated our lives. Jill Lepore takes us on a journey through the history of the Simulmatics Corporation, which in the 1960s attempted to control society through data analysis – first from 5th Avenue in New York for commercial marketing, then in the 1960 election campaign for John F. Kennedy, and at one point even in the Vietnam War. Their story impressively shows how technological developments and early forms of data analysis influenced the political landscape and continue to change our understanding of democracy and power to this day. But it also shows where the limits of the technologisation of democracy lie.